Organic fertilisers are a very valuable source of nutrients for plants and therefore efforts should be made to reduce losses as much as possible during the collection and storage process.

Following the Code of Good Agricultural Practice, it should be stated that all liquid and solid fertilisers and wastes produced on the farm should be stored in special sealed tanks or on slabs located in accordance with the requirements of the building law, at a suitable distance from buildings and the boundaries of the rural homestead and, above all, from the well, which is the source of water supply for humans and animals.

Organic fertilisers of animal origin include manure, slurry, slurry and chicken dung. They should be applied in doses depending on the fertilisation needs of the crop and the soil category (light, medium, heavy). The timing of application depends on the agronomic category of the soil and the crop grown. Manure is applied primarily to crops with a long growing season and which respond well to organic fertilisation. Application rates are 20-40 t/ha. On heavy and medium-heavy soils it is reasonable to apply manure in autumn, while on light and medium-light soils, in spring. Attention should be paid to spreading the manure evenly over the field surface and to ploughing – covering it with soil no later than the following day. Manure and slurry should preferably be introduced directly into the soil using spreader hoses connected to the tines of the cultivator. Once applied to the field surface, it should be mixed into the soil with a harrow, cultivator, or by ploughing, no later than the following day after application, in order to reduce nitrogen losses. Slurry can be applied pre-sowing and post-sowing to crops in the field and to grassland. For grassland, the manure is applied in early spring before the vegetation starts to grow and after the swaths have been harvested and in autumn. Recommended manure application rates are 25-30 m3/ha. In order to better utilise the nitrogen and potassium from the slurry, supplementary phosphorus fertilisation is necessary. As in the application of slurry and chicken dung, it is important to distribute the fertiliser evenly over the field.

Organic fertilisers should generally be used under plants with a long growing season, as they make the best use of the nutrients they contain, particularly nitrogen.

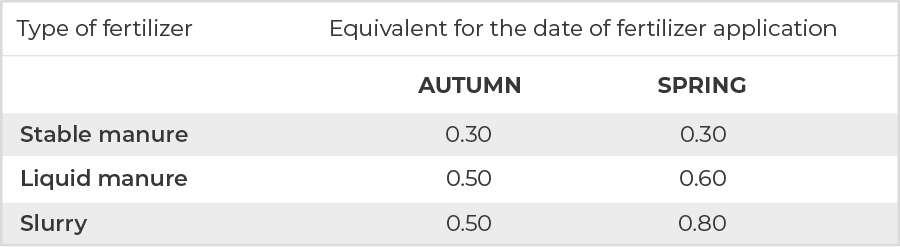

The doses of organic cattle and pig fertilisers should be determined according to their content of so-called action nitrogen. Acting nitrogen has the same fertilising effect as nitrogen from mineral fertilisers. When converting the total nitrogen of zoonotic fertilisers, as given in the Annex, into action nitrogen, the formula (according to CGAP) should be used: action nitrogen = total nitrogen x fertiliser equivalent (table below).

If the amount of any fertiliser applied on the farm, converted to total nitrogen, exceeds 170 kg of nitrogen per hectare, there is harmful over-fertilisation, which is prohibited by law. The farmer should then either reduce the stocking rate or, for example, enter into an agreement with neighbours to collect the excess manure.

Solid and liquid organic fertilisers should be statutorily applied to fields between 1 March and 30 November.

Slurry and manure should be applied to unploughed soil, preferably in early spring, but it is also permissible to apply these fertilisers post-harvest to plants, except for plants intended for direct human consumption, or shortly before they are fed to animals.

Efforts should be made to reduce the volume of slurry and manure produced on the farm by limiting the amount of water used to wash livestock housing to the minimum necessary and ensuring that drinkers are watertight.

7.9.1 Animal manure

Animal manure is a basic zoonotic organic fertiliser. It is a valuable source of stable and readily available nutrients and trace elements, improves soil structure and physical properties, helps maintain a constant humus level and counteracts humus loss. Permanently enriches the soil with organic matter, which improves its sorption properties and water-air relations. It stimulates the biological activity of the soil and mitigates the adverse effects of mineral fertilisation also by buffering sudden changes in pH. The mineral content of manure depends, among other things, on how it is stored. In simple terms, we distinguish between fresh manure, i.e. unfermented manure with a non-uniform structure and a broad C:N ratio of 30-25:1, and fermented manure. Manure fermentation should last 4-5 months. After this time, the manure acquires a relatively uniform, crumbly structure becoming a material that is easy to load and spread in the field. A partial mineralisation of organic matter takes place and the C:N ratio narrows to 15-20:1. This indicates that the fermentation process is more concerned with the transformation of nitrogen-free organic compounds than with those containing nitrogen. The rate and direction of chemical transformations in the manure depend on access to air. For proper fermentation, it is desirable to achieve anaerobic conditions, e.g. by kneading the manure. This also reduces the loss of ammonia produced during the fermentation process.

Fresh manure contains an average of 25% dry matter and the nutrient content of its fresh matter is: 0.5% nitrogen (N), 0.25% phosphorus (P2O5) and 0.6% potassium (K2O), as well as some calcium, magnesium and micronutrients.

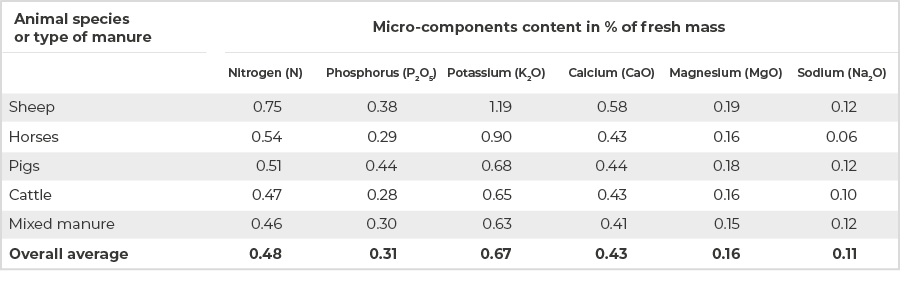

The chemical composition of manure in Poland according to animal species (Maćkowiak Cz., IUNG, Puławy, 2002) is presented in the table below:

The advantage of manure is its long period of effect. Nutrients can be released for several years after application. Their greatest bioavailability occurs in the second year after mixing it into the soil. In sandy soils, mineralisation of manure is faster – here a strategy should be adopted to take this fact into account.

7.9.2 Slurry and liquid manure

Slurry can replace animal manure. Based on the degree of dilution, a distinction is made between dense slurry >8% dry matter and thin slurry <8% dry matter.

Slurry having 10% dry matter contains 0.38% N, 0.20% P2O5, 0.41% K2O, 0.32% CaO and 0.09% MgO in fresh matter.

Slurry – fermented urine and manure leachate – is a one-sided fertiliser that is almost completely devoid of phosphorus. It contains on average 1-3% dry matter, 0.3-0.6% N, 0.68-0.83% K2O and less than 0.04% P2O5.

Slurry and manure poured in an uncontrolled manner pose a threat to the natural environment. European Union legislation allows the application of natural fertilisers (slurry, manure, slurry) up to a maximum of 170 kg of nitrogen (N) in pure component per hectare of agricultural land. The requirements for agricultural buildings for the storage of manure, slurry and liquid manure are given in the Act of 10 July 2007 on Fertilisers and Fertilisation.

7.9.3 Chicken manure

The main sources of chicken manure are laying or broiler farms – in this case, often kept on straw. Laying hen manure should preferably be mixed with straw before use – this will allow it to be evenly distributed over the field. Its application should be carried out immediately after removal from the poultry shed or after storage for as short a time as possible. Excessive doses can cause salinisation of soils, especially lighter soils, with all the consequences for impaired plant development.

Chicken manure contains a very high concentration of nutrients (NPK), including up to almost three times more nitrogen than cattle or pig manure. In bird manure, nitrogenous compounds occur as protein compounds, substances with ammonium ion (NH4+) and uric acid. The high content of easily decomposable uric acid and ammonium compounds creates the risk of nitrogen escaping easily into the atmosphere. Depending on air temperature, soil pH and application method, nitrogen losses can be as high as 60%. Phosphorus is mainly present in mineral compounds and potassium is easily soluble in water. Valuable micronutrients contained in chicken include boron and molybdenum. The composition depends on the species of poultry and the litter used, so it should be carefully examined each time.

As a standard, manure from laying hens, containing about 40% dry matter, is assumed to contain 1.3% N, 0.4% P2O5, 0.6% K2O, while that from ducks and geese is assumed to contain about 0.8% N, 0.5% P2O5, 0.4% K2O.

Plants are able to utilise most of the nutrients already in the first year, and the after-effect of chicken manure does not last longer than two years.